Ten remarkable new marine species from 2018

Release date: March 19th 2019

- Okinawan’s Octocoral Reef Flowers, Hana hanagasa

- The Stromatolite Tanaid, Sinelobus stromatoliticus

- The Antarctic Legged-Leech, Ambulobdella shandikovi

- The Hawaiian Spurdog, Squalus hawaiiensis

- The Hong Kong Sea Dragon, Hoilungia hongkongensis

- The Confusing Blanket Hermit Crab, Paguropsis confusa

- The ‘Japan-pig’ Pygmy Seahorse, Hippocampus japapigu

- The Hairy-footed ‘Baggins’ Shrimp, Odontonia bagginsi

- The Sponge-loving Red Alga, Ptilophora spongiophila

- The Southern Tough-guy Worm, Parallelolebes virilis

Okinawan’s Octocoral Reef Flowers

Hana hanagasa Lau, Stokvis, Van Ofwegen & Reimer, 2018

Octocorals are often seen as beautiful sea fans that grow conspicuously on coral reefs, but they actually come in many shapes and colours; many are much more cryptic and remain hidden from science. This new species, on the other hand, is one of those hidden in plain sight cases. Hana hanagasa is not only very beautiful, but stands out for the flower-like resemblance of their conspicuous bright polyps. For this reason, the new genus was named “Hana”, which means flower in the Japanese language. Hana hanagasa was found in Okinawa only, and is named after the traditional Okinawan headpiece worn by female dancers, “hanagasa”. This headpiece symbolises the flower of Okinawa, the hibiscus, and has shades of blue that represent waves of the Okinawan Ocean. Research on octocorals is far from finished and new discoveries are still being made. This new species belongs to a larger group of octocorals called Stolonifera, which is one of the lesser-studied octocoral groups. This new discovery emphasizes the need for octocoral taxonomy, as it sheds more light on our understanding of this group and ultimately coral reef biodiversity.

The Stromatolite Tanaid

Sinelobus stromatoliticus Rishworth, Perissinotto & Błażewicz, 2018

In sludgy tidal pools along the South African coastline, stromatolite habitats have been discovered in the past two decades. What is remarkable about this is that these pools closely resemble the earliest and most extensive ecosystems known from the fossil record, some of which date as far back as 3.5 billion years. Stromatolites, or layered rocks, are sedimentary deposits that are precipitated by microalgae. Living examples are rare today because modern seawater conditions have changed and because most microbial mats which can potentially form stromatolites are now extensively grazed or bioturbated by metazoans. It is therefore surprising that a diverse metazoan community dwells within the South African stromatolites without destroying this layered deposit.

Amongst these species lives a tube-dwelling tanaid, which was previously unknown to science, the so-called Stromatolite Tanaid (Sinelobus stromatoliticus). Interestingly, the Stromatolite Tanaid eats very little of the microalgae which builds its stromatolite home. Instead, these small (less than 3 mm) grazers use the stromatolite matrix as a refuge to escape some of the harsh conditions of the intertidal zone. This tanaid also comprises part of the Sinelobus consortium, which was once considered globally cosmopolitan but recently we have realised, is diversified amongst unique, geographically distinct ecosystems (seven Sinelobus species have been described so far).

Scientists are eagerly searching within these ancient analogue stromatolite ecosystems for other unique treasures, but so far, the charismatic Stromatolite Tanaid is the “posterchild” of its home and has been an exciting local discovery in South Africa and for the tanaid taxonomy community during 2018.

The Antarctic ‘Legged’ Leech

Ambulobdella shandikovi A. Utevsky & S. Utevsky, 2018

Leeches (Annelida: Hirudinea) are usually thought to be bloodsucking ectoparasites associated with freshwater ecosystems. However, this generally accepted point of view is rather wrong. Fish leeches (Picsicolidae) occur in the sea including the cold waters of the Antarctic. Moreover, a few of them have been recorded from deep-sea habitats. Many deep-sea animals (e.g. fishes) are known for their unusual appearance. The same may be expected from fish leeches.

In 2018, the deep-sea fish leech Ambulobdella shandikovi was described from the Antarctic deep sea at depths of 1221–1,433 m, attached to Whitson’s grenadier Macrourus whitsoni (Regan). The leech is unusual both because of its habitat and because of weird morphology. Ambulobdella shandikovi bears segmentally arranged limb-like projections. The name of the new genus alludes to this, coming from a combination of ‘ambulare’ meaning ‘to walk’ in Latin and ‘bdella’ meaning ‘a leech’ in Greek.

Most known leeches do not have external appendages. Although plesiomorphic limbs (parapodia), antennae and palps were lost in the ancestors of leeches, the prominent paired segmentally arranged ventrolateral tubercles of A. shandikovi are reminiscent of polychaete parapodia or onychophoran limbs. A. shandikovi is a unique marine species in respect of both its weird appearance and its extreme habitat.

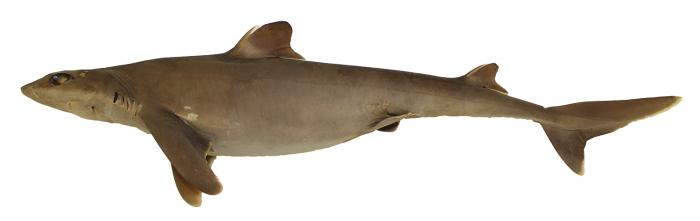

The Hawaiian Spurdog

Squalus hawaiiensis Daly-Engel, Koch, Anderson, Cotton & Grubbs, 2018

Seemingly impossible to tell apart from its Japanese siblings, the only spurdog population inhabiting the Hawaiian Archipelago eventually turned out to be a species new to science, after scientists conducted an elaborate identification approach, simultaneously involving physical measurements, standard DNA markers and an additional fast-evolving mitochondrial gene.

Deep-water sharks are often subject to high fishing pressure as bycatch and they are known to have long reproductive intervals (12–24 months) and slow growth rates, compounding the depleting effect of fishing. Unfortunately, apart from being depleted as bycatch, this new endemic species of deep-water dogfish also shows the lowest rate of genetic diversity known in a shark population to date.

The Hong Kong Sea Dragon

Hoilungia hongkongensis Eitel, Schierwater & Wörheide, 2018

Hoilungia hongkongensis, the 'Hong Kong Sea Dragon', is only the second species formally described in 135 years in the so far monotypic marine phylum Placozoa, where Trichoplax adhaerens has been the only described species until 2018.

Although numerous placozoans that were found worldwide were morphologically assigned to T. adhaerens in the past, only in recent years, single gene-based characterization identified a large genetic diversity in the Placozoa. Formally describing deeply diverging lineages as new species was so far hampered by a lack of diagnostic morphological characters. This deficiency was calling for a new approach to delineate putatively distinct placozoan species without diagnostic morphological characteristics.

The authors of the first description of H. hongkongensis used purely comparative genomics, a so-called ‘taxogenomics’ approach, to define this new placozoan species. Based on the comparison of the genome of the name-giving placozoan strain from Hong Kong and the genome of T. adhaerens, it was concluded that genomic differences on various levels (genome structure, reproductive isolation, genetic distances) support the distinction and description of a new species. When compared to genetic distances within other non-bilaterian animal phyla (Porifera, Cnidaria, Ctenophora) as well as with Chordata, the genetic distances between the placozoan genomes indicated differences at least on the genus level. Consequently, the new placozoan species was assigned to a new genus.

The description of a new placozoan species and a new genus marks the beginning of the establishment of a long missing systematics in the Placozoa and the new ‘taxogenomics’ approach is promising to help other taxonomists dealing with cryptic groups.

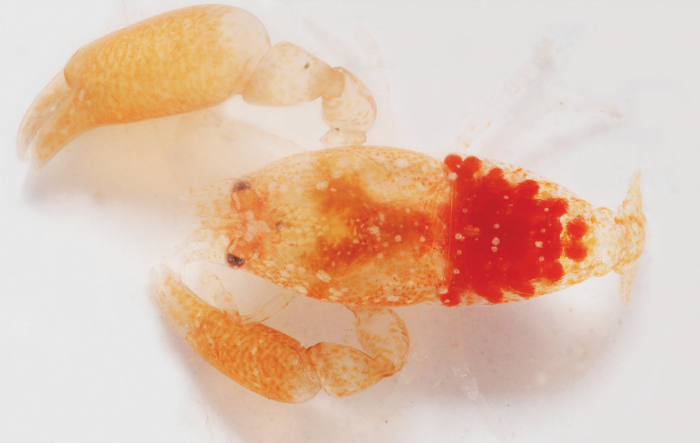

The Confusing Blanket Hermit Crab

Paguropsis confusa Lemaitre, Rahayu & Komai, 2018

Unlike ‘ordinary’ hermit crabs, blanket-hermit crabs do not seek an empty shell to shelter their soft, unprotected bodies, which is later swapped for a larger one as the crustacean grows in size. Instead, species like the recently discovered Paguropsis confusa use their specialised chelate fourth legs to grab and stretch the thin-walled body of a sea anemone to cover themselves. In this cosy symbiosis, the two animals grow together, allowing for the anemone’s spreading zoophytes to form a blanket, which the crustacean could easily draw to completely cover its head, if need be. While the study describes four newly identified species, including Paguropsis confusa, previously there had only been one known blanket-hermit crab in existence, discovered back in the 19th century.

The species name comes from the latin ‘confuso’, meaning confusion or disorder, refers to the morphological confusion that had prevented the unmasking of this and other new blanket hermit crabs, hidden under the name P. typica.

The ‘Japan-pig’ Pygmy Seahorse

Hippocampus japapigu Short, Smith, Motomura, Harasti & Hamilton, 2018

The size of a grain rice, this recently discovered species of strikingly coloured pygmy seahorse blends in successfully with the algae-covered rocks in the shallow waters, which it inhabits near Hachijo-jima Island, Japan. Interestingly, even before the species was officially described, the local divers had already likened the creature to a “tiny baby pig”, which prompted the authors to come up with a species name, which translates to “Japan Pig”. Another interesting fact about the species is that it has only one gill positioned on the upper back, rather than two below each side of the head.

The Hairy-footed ‘Baggins’ Shrimp

Odontonia bagginsi de Gier & Fransen, 2018

Having amazed its discoverer with its distinctively hairy feet, this new species of shrimp, discovered at the Indonesian islands of Tidore and Ternate, quite understandably received the name of Middle Earth's greatest Halfling family, ‘Baggins’, known from the famous works of J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The new species was described along with another in the same genus during the first author’s first degree. Werner de Gier says: “Being able to describe, draw and even name two new species in my bachelor years was a huge honour. Hopefully, we can show the world that there are many new species just waiting to be discovered, if you simply look close enough!"

The Sponge-loving Red Alga

Ptilophora spongiophila G.H.Boo, L.Le Gall, I.K.Hwang, K.A.Miller & S.M.Boo, 2018

Madagascar is one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots due to its diverse, endemic, and highly threatened biota. However, the Malagasy marine algal flora is one of the least studied in the Indian Ocean. Endemism has received little attention because of the limited number of taxonomic studies on seaweeds from Madagascar. Ptilophora is an agar-producing red algal genus occurring mostly in subtidal habitats in the Indo-Pacific Ocean. Most species are rarely encountered, occurring in subtidal habitats down to a depth of 100 m. Ptilophora spongiophila, up to 26 cm tall, is heavily coated with sponges (hence its specific name). It appears to be common in southeastern Madagascar at depths of 5-30 m.

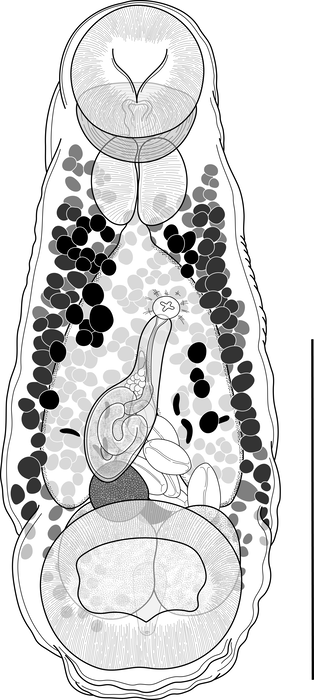

The Southern Tough-guy Worm

Parallelolebes virilis Martin, Ribu, Cutmore & Cribb, 2018

This species, for which a new genus was proposed, was described in a survey of the endoparasitic trematodes (flukes) of the subfamily Opistholebetinae (family Opecoelidae) occurring in pufferfishes, globefishes, toadfishes and porcupinefishes (families Tetraodontidae and Diodontidae) in Australian waters. Parallelolebes virilis is the first species in this group to be found in a different, but related, family of fishes, the leatherjackets (family Monacanthidae). It is known only from the horseshoe leatherjacket, Meuschenia hippocrepis, which is endemic to southern Australian waters. The host specimen was line-fished from the jetty at Stanley, Tasmania in 1999 and the worm remained preserved but undescribed for almost two decades. Relative to other opecoelids, these opistholebetines are usually large, fleshy, chunky worms. Parallelolebes virilis is easily the smallest of this group, obtaining a maximum length of just over 1 millimetre. Despite its diminutive size, it was named the tough-guy worm, the species name ‘virilis’ meaning ‘manly’ in Latin, because it is the only species in the group that gets about in leatherjackets.

Sources

Okinawan’s Octocoral Reef Flowers

Original source

Lau, Y. W.; Stokvis, F. R.; Van Ofwegen, L. P.; Reimer, J. D. (2018). Stolonifera from shallow waters in the north-western Pacific: a description of a new genus and two new species within the Arulidae (Anthozoa, Octocorallia). ZooKeys. 790: 1-19. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.790.28875

Contacts:

Yee Wah Lau (lauyeewah87@gmail.com) (English, Dutch), co-author of the new species

James Davis Reimer (jreimer@sci.u-ryukyu.ac.jp) (English, Japanese), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1304878&pic=136426

The Stromatolite Tanaid

Original source:

Rishworth, G. M.; Perissinotto, R.; Błażewicz, M. (2018). Sinelobus stromatoliticus sp. nov. (Peracarida: Tanaidacea) found within extant peritidal stromatolites. Marine Biodiversity. 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-018-0851-3

Contact:

Magdalena Błażewicz, University of Łódź (magdalena.blazewicz@biol.uni.lodz.pl), co-author of the new species

Gavin Rishworth, Nelson Mandela University (gavin.rishworth@gmail.com), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1054905&pic=136439

The Antarctic ‘Legged’ Leech

Original source:

Utevsky, A.; Utevsky, S. (2018). New Antarctic deep-sea weird leech (Hirudinida: Piscicolidae): morphological features and phylogenetic relationships. Systematic Parasitology. 95(8-9): 849-861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-018-9816-y

Contact:

Andriy Utevsky (andriy.utevsky@karazin.ua), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1324277&pic=13643

The Hawaiian Spurdog

Original source:

Daly-Engel, T. S.; Koch, A.; Anderson, J. M.; Cotton, C. F.; Grubbs, R. D. (2018). Description of a new deep-water dogfish shark from Hawaii, with comments on the Squalus mitsukurii species complex in the West Pacific. ZooKeys. 798: 135-157. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.798.28375

Contact:

Toby S. Daly-Engel (tdalyengel@fit.edu), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1320613&pic=136430

The Hong Kong Sea Dragon

Original source:

Eitel, M., W.R. Francis, F. Varoqueaux, J. Daraspe, H.J. Osigus, S. Krebs, S. Vargas, H. Blum, G.A. Williams, B. Schierwater & G. Worheide. (2018). Comparative genomics and the nature of placozoan species. Plos Biology, 16(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2005359

Contact:

Michael Eitel (m.eitel@lmu.de), co-author of the new species

Gert Wörheide (woerheide@lmu.de), co-author of the new species

Image availabe at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1316502&pic=135471

The Confusing Blanket Hermit Crab

Original source:

Lemaitre, R.; Rahayu, D. L.; Komai, T. (2018). A revision of “blanket-hermit crabs” of the genus Paguropsis Henderson, 1888, with the description of a new genus and five new species (Crustacea, Anomura, Diogenidae). ZooKeys.752: 17-97. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.752.23712

Contacts:

Dr Rafael Lemaitre (lemaitrr@si.edu), co-author of the new species

Press release:

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2018-04/pp-fnb042318.php

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1249809&pic=136427

The ‘Japan-pig’ Pygmy Seahorse

Original source:

Short, G.; Smith, R.; Motomura, H.; Harasti, D.; Hamilton, H. (2018). Hippocampus japapigu, a new species of pygmy seahorse from Japan, with a redescription of H. pontohi (Teleostei, Syngnathidae). ZooKeys. 779: 27-49. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.779.24799

Contact:

Graham Short (gshort@calacademy.org), co-author of the new species

(Additional) image(s) available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1288522&pic=136431

The Hairy-footed ‘Baggins’ Shrimp

Original source:

De Gier, W.; Fransen, C. H. (2018). Odontonia plurellicola sp. n. and Odontonia bagginsi sp. n., two new ascidian-associated shrimp from Ternate and Tidore, Indonesia, with a phylogenetic reconstruction of the genus (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae). ZooKeys. 765: 123-160. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.765.25277

Contact:

Werner de Gier (werner.degier@naturalis.nl), co-author of the new species

Press release:

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2018-06/pp-iah060718.php

(Additional) image(s) available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1258692&pic=136428

The Sponge-loving Red Alga

Original source:

Boo, G. H.; Gall, L. L.; Hwang, I. K.; Miller, K. A.; Boo, S. M. (2018). Phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of Ptilophora (Gelidiales, Rhodophyta) with descriptions of P. aureolusa, P. malagasya, and P. spongiophila from Madagascar. Journal of Phycology. 54(2): 249-263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12617

Contact:

Line Le Gall (line.le-gall@mnhn.fr), co-author of the new species

Ga Hun Boo (gahun.boo@mnhn.fr), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1325046&pic=136442

The Southern Tough-guy Worm

Original source:

Martin, S. B.; Ribu, D.; Cutmore, S. C.; Cribb, T. H. (2018). Opistholobetines (Digenea: Opecoelidae) in Australian tetraodontiform fishes. Systematic Parasitology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-018-9826-9

Contact:

Storm Martin (storm.martin@uqconnect.edu.au), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1305964&pic=136432