Ten remarkable new marine species from 2021

Release date: March 19th 2022

- The Hidden Horniman Mysid, Heteromysis hornimani

- The Cebimar Moon Jellyfish, Aurelia cebimarensis

- The Emperor Dumbo, Grimpoteuthis imperator

- The Yokozuna Slickhead, Narcetes shonanmaruae

- The Quarantine Shrimp, Periclimenaeus karantina

- The Japanese Twitter Mite, Ameronothrus twitter

- The Jurassic Pig-Nose Brittle Star, Ophiojura exbodi

- Ramari’s Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon eueu

- The Balloon Backpack Isopod, Akrophryxus milvus

- Winter’s Basket Coccolithophore, Syracosphaera winteri

The Hidden Horniman Mysid

Heteromysis (Olivemysis) hornimani Wittmann & Abed-Navandi, 2021

For more than a decade, nobody at the museum had any idea that the unusually fast-moving, zig-zagging crustaceans that they were feeding to the fish in their aquarium was actually a species unknown to science.

Smaller than a child’s fingernail, this new species of marine mysid crustacean was discovered in a humble tank at the Horniman Museum and Gardens, in Forest Hill, south London, where it has spent at least the past 12 years hiding in plain sight and “breeding like mad”. The Horniman Aquarium showcases marine environments from around the world, from British ponds to Fijian coral reefs.

The mysid shrimp is now named Heteromysis hornimani, in honour of its place of discovery, by Prof. Karl Wittmann and Dr Daniel Abed-Navandi, both marine biologists in Vienna. The species is thought to have “hitchhiked” to the museum on an ocean rock many years ago. The species has not yet been found in nature (although some of the data suggests it is likely to originate in the Caribbean), but it is well-established in every tank of the aquarium in the museum, where they like to “zip around” and “zig-zag” in a figure of eight.

“We’ve used them as a food source because they breed so prolifically,” said aquarium curator Dr Jamie Craggs, who had no idea they were an undiscovered species. “I’ve been here 12 years and they’ve been here all that time.”

Apparently, the new species has a characteristic swimming style. They zig-zag backwards and forwards in a figure of eight pattern, and this is one of their defining characteristics. They also have a peculiar perpendicular orientation of only the second pleopod. A feature which is easily visible (see photo) and will help in identification by both aquarists and in finding the species in its natural habitat.

The discovery was made after the museum answered researcher Abed-Navandi’s request for mysid crustaceans from around the world. Samples from the Horniman Aquarium were sent for study and the Hidden Horniman Mysid took its final step towards discovery.

The Cebimar Moon Jellyfish

Aurelia cebimarensis Lawley, Gamero-Mora, Maronna, Chiaverano, Stampar, Hopcroft, Collins & Morandini, 2021

Known as moon jellyfish, species of the genus Aurelia are among the most popular jellyfish. They are cultivated in aquaria around the world and appear as a classic example of jellyfish in textbooks. They are also among the most studied jellyfish, often appearing in the international media because they can form large population aggregates (known as blooms) which, in the case of moon jellyfish, occur mainly in colder regions.

They are widely known, but rather rare in Brazilian coastal waters. This new species, Aurelia cebimarensis, was named after Centro de Biologia Marinha (CEBIMar) of the University of São Paulo, Brazil, which is exactly where the type specimen was collected. The CEBIMar is a well-respected international research institute for marine biology, and many of the authors of the study have depended heavily on these facilities for both their education and research.

Since the 19th century, taxonomists have had difficulty separating the supposed species of Aurelia, mainly due to their morphological similarity. Species are traditionally described based on physical characters, such as colour, size and shape of the body and its structures, both macro and microscopic. In many cases, discovering these differences in morphological characters between species is incredibly difficult. In the last 20 years studies have shown that there are cryptic species of Aurelia, and that in certain cases, morphology can vary by environment.

Analysis of moon jellyfish from different parts of the world, both from specimens kept in aquarium culture and those preserved in museum collections allowed progress to be made in the understanding of this complex group of animals. The authors made use of the information contained in the DNA of the species, managing to distinguish them using molecular diagnoses, and in this way, they were able to recognize 28 species in the genus, only seven of which were already known to science. Ten of these have now been described as new, including Aurelia cebimarensis, dedicated to the Centro de Biologia Marinha (CEBIMar) of the University of São Paulo.

The need to recognise and have a means to communicate about the diversity of species is incredibly important, even more so in the current scenario of large and rapid global environmental changes. This immense study has forged a path to a greater understanding of the many species of moon jellyfish found globally.

The Emperor Dumbo

Grimpoteuthis imperator Ziegler & Sagorny, 2021

This new species is a dumbo octopus, so named for the pair of fins which resemble the oversized ears of Disney’s cartoon elephant, and which the animals use to ‘fly’ through the depths of the oceans. This beautiful species was described using a single specimen captured in 2016 in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean at around 4000 m deep. As soon as the first author, Alexander Ziegler, laid eyes on it, he thought it was likely to be a new species. These animals are rarely collected intact and given the remoteness of the sampling location and the depth sampled, Ziegler knew the specimen was important.

He decided that this would be a great opportunity to study one of these rare cephalopods using a minimally invasive approach. The team took photographs, made external measurements and took DNA samples on-board the ship, and then the specimen was preserved for further study back in the laboratory.

The team then analysed the sole specimen they had using innovative non-invasive imaging techniques rather than traditional dissection in order to assess its morphology and anatomy. They used high-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and high-resolution micro-computed tomography (µCT) in order to visualize all characters relevant for a full species description.

These analyses - the first time such a large animal has ever been described through largely non-invasive methods - showed that the dumbo octopus is a new species in the genus Grimpoteuthis. Ziegler and his colleague Christina Sagorny, a graduate student at the University of Bonn, gave it the name Grimpoteuthis imperator - or Emperor dumbo - after the Emperor Seamounts, an underwater mountain range off Japan where the animal was collected.

Ziegler says “it was particularly rewarding to see my master student's work featured prominently in the scientific literature, and we hope that the minimally invasive approach established by us for description of marine megafauna will find followers in the scientific community.”

The Yokozuna Slickhead

Narcetes shonanmaruae Poulsen, Ida, Kawato & Fujiwara, 2021

This new species of fish belongs to the family Alepocephalidae (slickheads), and it was described from four specimens collected around depths of 2500 m in Suruga Bay, Japan. The new species is truly colossal (for a slickhead!), reaching 1.4 metres in length and weighing in at up to 25kg. For this reason, the new species has been named after Japan’s elite sumo wrestlers. The Yokozuna Iwashi, is the proposed Japanese common name and refers to the highest rank in sumo wrestling in Japan - ‘Yokozuna’.

Although most slickheads are benthopelagic or mesopelagic and feed on smaller gelatinous zooplankton, study of this new species showed it feeds on other fish, and video footage recorded using a baited camera deployed at a depth of 2572 m in Suruga Bay revealed this fish is an active swimmer. The scavenging ability and broad gape of the Yokozuna Sumo Slickhead might be correlated with its colossal body size and high trophic position. The food chain is organised into five trophic levels, with apex predators being ranked closest to five. The newly-discovered fish was shown to have a very high trophic level of 4.9.

Yoshihiro Fujiwara, of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), emphasised the sheer size of the new species compared to others of the same family. He said: “This new species is the biggest in the family Alepocephalidae. The average size of species in this family is about 30 to 40cm. We believe that this slickhead is probably a top predator in the deepest part of Suruga Bay.”

“Accordingly, we propose the name Yokozuna Iwashi as being indicative of the large body size and the high trophic position of the newly described species.”

The new species’ scientific name, Narcetes shonanmaruae, honours the ‘Shonan maru’, the ship from which the new species was caught.

The Quarantine Shrimp

Periclimenaeus karantina Park & De Grave, 2021

Species of the shrimp genus Periclimenaeus, are known to dwell inside various sponges or ascidians, which are assumed to be excellent shelters from predators and potentially even a source of food to the shrimps. This attractive new species has been appropriately named Periclimenaeus karantina, which is from the Greek karantina (καραντίνα) meaning ‘quarantine’ referring not only to the lifestyle of the new species, being isolated in the host ascidian species, but most aptly to the quarantine of human society due to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), during which time the paper was written.

The first author and collector of the species, Jin-Ho Park, was planning to spend a whole year working with co-author and shrimp expert Sammy De Grave at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, he had only spent two weeks at the museum before the country went into lockdown. As the University was closed for much of the year, this meant that they had to set up a home lab to allow the work to progress, which it did, just in a different way. Local travel restrictions were such that everything was done via Skype and email, despite both co-authors’ houses being less than 5 km from each other. So, just like the shrimps that were described in this paper, the co-authors, were isolated, quarantined, and apart from one another while the work was undertaken.

In Korea, few studies have focused on these shrimp, and only one species had previously been reported from the region. This new study increased the number of species known in Korean waters to four. The other new species in the same paper was named P. apomonosi, from the Greek word meaning isolation and seclusion, equally double entendre.

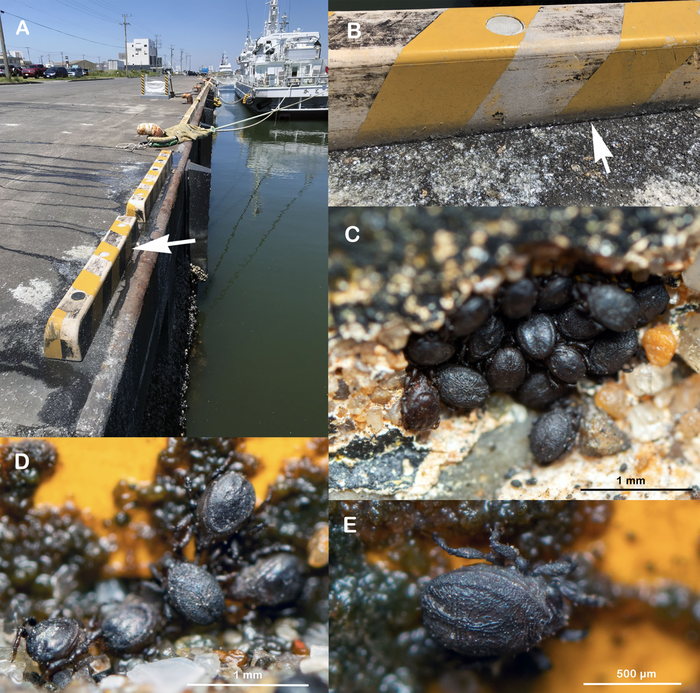

The Japanese Twitter Mite

Ameronothrus twitter Pfingstl & Shimano, 2021

This tiny mite, just half a millimetre long, was first spotted on a wharf in Honshu, Japan by Takamasa Nemoto (@yatsume_project), a photographer and nature enthusiast. After not having much luck fishing that day, he decided to photograph the mites he saw crawling on the wharf and posted the images on Twitter. The tweets were seen by Japanese scientist, Satoshi Shimano, who studies mites, and he quickly recognized the genus of the mite but not the species. The scientist and photographer communicated by twitter and were able to collect additional mites for closer study, and discovered they were an undescribed species! In fact, the photographs labelled C, D, E are some of the original photos that were posted on Twitter.

This genus of mites lives on shorelines in the region between high and low tides where they feed on a wide variety of food items. So far, this new species has only been found on man-made concrete structures on a wharf at a fishing port. Scientists think these mites may have originally lived on rocks, since the lichen, fungi, and algae they feed on grow on both rocks and concrete. On cold days, the mites are found gathered together in cracks in the concrete. Huddling together like this may help protect them from the cold. The discovery of this new species is a fantastic example of the power that both citizen science and social media have to fuel new discoveries.

The Jurassic Pig-Nose Brittle Star

Ophiojura exbodi O’Hara, Thuy & Hugall, 2021

Ophiuroids, or brittle stars, are a group of more than 2,000 species of starfish relatives with long, serpent-like arms. Thanks to their hard-armored skeletons, brittle stars have a rich micro-fossil record and are known to have evolved more than 270 million years ago, 10’s of millions of years before the first dinosaurs. They are found at all ocean depths and are especially widespread in the deep sea.

This new species is a “phylogenetic relic”. Like the coelacanth, it is a surviving species of an ancient group that has otherwise gone extinct. In fact, the new species diverged from all other brittle stars 180 million years ago! To put that into perspective, this brittle star is more distantly related to other brittle stars than a human is to a kangaroo!

This brittle star species was discovered living on a seamount off New Caledonia. Only one individual has ever been collected so far. It was instantly recognised as a unique brittle star thanks to its 8 arms, unusual arm spine articulations that resemble pig noses, and the particularly spiny mouth. It uses its 8 arms to crawl across the seafloor to hunt small prey and scavenge. The species name “exbodi” refers to the French Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle EXBODI expedition during which this new species was discovered.

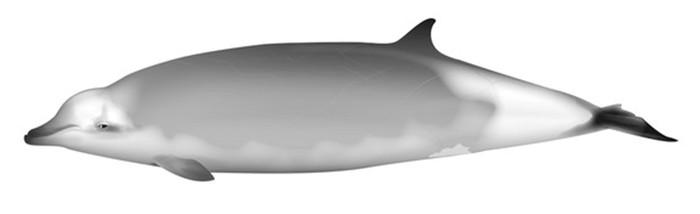

Ramari’s Beaked Whale

Mesoplodon eueu Carroll et al., 2021

The ocean is one of the last great frontiers on Earth, and to this day it remains largely unexplored. It is estimated that there are around 1.5 million species still waiting to be discovered in the world’s oceans. There are few more obvious demonstrations of the limitations of our knowledge of sea life than the discovery of a new whale species.

Indigenous culture and science combined to confirm that this 5m (15 ft) beaked whale was a new species. A dead female whale washed up on the west coast of Te Waipounamu (South Island), Aotearoa New Zealand and was found by the local iwi (tribe) of Ngāti Māhaki. The whale was examined by renowned Mātauranga Māori whale expert Ramari Stewart, who was raised by her elders in the traditional Māori knowledge of the sea. She recognized the whale as unique and worked with locals and the New Zealand Department of Conservation to prepare the bones for archive at Te Papa Tongarewa Museum. A team of international collaborators examined this whale along with other specimens from South Africa and found that they were morphologically and genetically different from all other whale species, and so Ramari’s beaked whale was described.

The common name and the scientific name honor Indigenous communities in South Africa and Aotearoa New Zealand and were selected in consultation with these groups. The majority of South African whale strandings occur on the land of the Khosian people, so the scientists worked with the Khosian council to choose the word //eu//‘eu, latinised to ‘eueu’, meaning ‘big fish’, as the species’ name. The common name honors Ramari Stewart, the first time a cetacean has been named after an Indigenous woman, and “Ramari” also translates to ‘a rare event’ in Te Reo, the Māori language, in reference to the elusive nature of beaked whales. A video by the University of Auckland explores the etymology of this species.

The discovery, description, and naming of this new species serves as a beautiful example of the impact Indigenous culture and science can have when combined. It also serves as a reminder that if humans are only now encountering a new whale species, who knows what other mysteries the ocean holds, just waiting to be discovered.

The Balloon Backpack Isopod

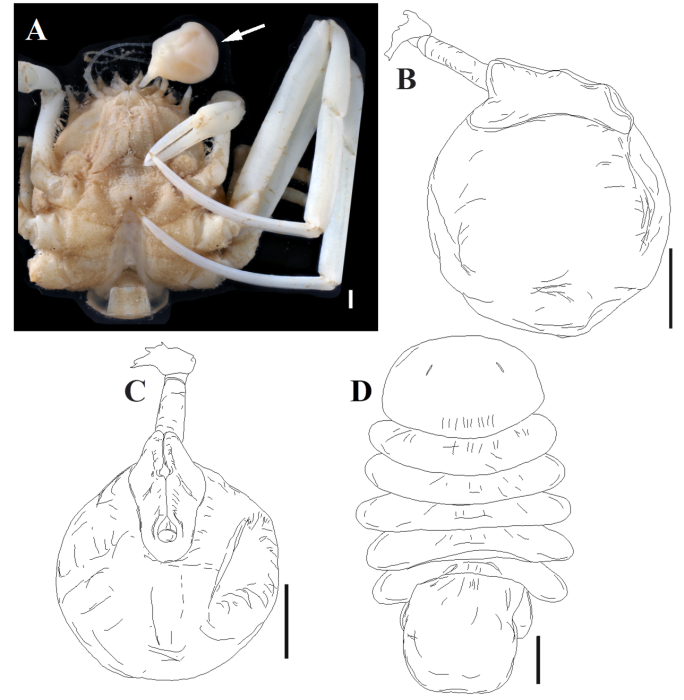

Akrophryxus milvus Williams & Boyko, 2021

Isopods are a group with over 10,000 species of crustaceans that includes familiar terrestrial species like pill-bugs, roly-polies, and wood lice. Despite being commonly found alongside insects, terrestrial isopods are more closely related to crabs, shrimp, and barnacles than they are to insects. The majority of isopod species are marine, and hundreds of species are parasites of other crustaceans. This new species belongs to a family of marine parasitic isopods called Dajidae or “backpack isopods” because they are typically flattened and attached to the back of their shrimp or crab hosts (giving the appearance that the host is wearing a backpack). They survive by piercing the exoskeleton of their host and feeding on its blood.

However, even among backpack isopods, the new species is a real oddity. First, it is not dorsoventrally flattened and so does not look like a backpack at all - its round, sac-like body is more reminiscent of a balloon than a backpack. Second, it does not attach to the back of its crab host, rather it attaches to its host’s antennule and forms a shield-shaped plate around this structure. In fact, its species name ‘milvus’ is derived from the Latin word for ‘kite’ in reference to this structure, which is shaped like the kite shields commonly used by soldiers in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. This species was so different from all other isopods that it was also placed in its own new genus, Akrophryxus, from the Greek ‘akro’ meaning ‘limb’ and ‘phryxus’, a reference to prince Phryxus who made the golden fleece in Greek Mythology, which is a common ending for other parasitic isopod genera.

With its round body and hidden appendages, this remarkable new species bears little resemblance to other parasitic isopods, and it takes a keen eye to realize it is in fact a modified backpack isopod. One such hint at its kinship is that only the females (images A-C) are balloon-shaped, while the males (image D) reside INSIDE the body of the female, and look more like a typical parasitic isopod with a flattened body and 6 pairs of legs. This discovery of this bizarre new species sheds light on the amazing morphological diversity that has evolved as these isopods adapt to a range of specialized parasitic lifestyles.

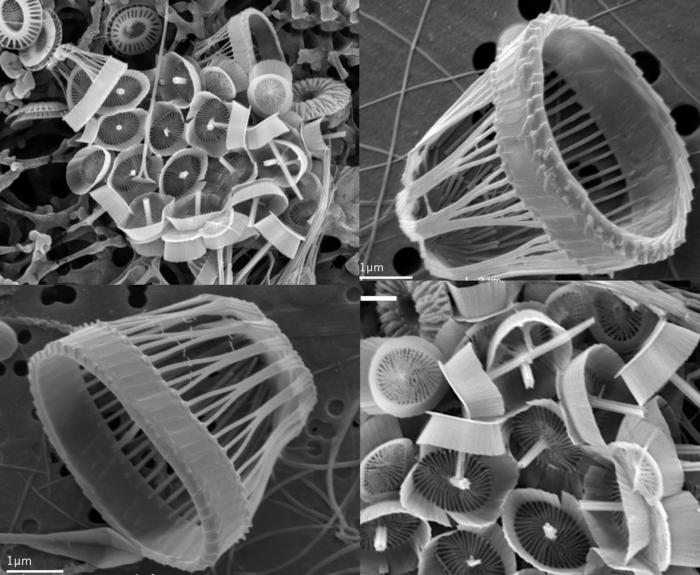

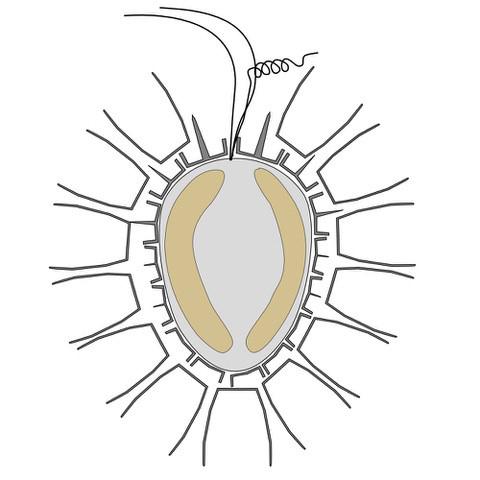

Winter’s Basket Coccolithophore

Syracosphaera winteri Keuter, Koplovitz, Zingone, J.R.Young & Frada 2021

These beautiful structures are built by microscopic plant-like organisms called coccolithophores. Coccolithophores are single celled creatures that live in huge numbers in the surface waters of the ocean all around the world. They photosynthesize, producing a large proportion of the world’s oxygen, and continually build detailed, geometric structures called coccoliths out of calcium carbonate, like those in the images seen here. Exactly why they build coccoliths is still a mystery, but it is thought they might protect them, help them regulate buoyancy, or help them direct sunlight.

At about 1/100 millimetre wide, what coccolithophores lack in size they make up for in numbers. They are some of the most abundant organisms in the ocean and have been for more than 200 million years. Their constant creation of coccoliths makes them a key component of the carbon cycle. In fact, coccoliths are the main component of many chalk deposits around the world, including the white cliffs of Dover, which are deposits of coccoliths from the Cretaceous (about 66–100 million years ago). These cliffs that are now over 300 m tall in some areas were formed by the continual accumulation of trillions of coccoliths at a rate of about half a millimetre every ten years.

This new species is one of the most extraordinary coccolithophores of all. It continually excretes these delicate, miniature basket-like coccoliths that are less than 5 µm wide. Syracosphaera winteri is extremely rare, and only a few specimens have ever been found. Coccoliths of it were first observed by Professor Amos Winter while he was working on his PhD in the 1970’s in the Gulf of Eilat, but it is only recently, 40 years later, that complete specimens were found and described for the first time. This new species was named in his honour. In life, the basket-like coccoliths would be arranged in a complete sphere around the cell, with the openings outwards. Sadly, they typically collapse when prepared for microscopy, and a complete specimen has not yet been found but the drawing shows what scientists believe it would look like.

Sources

The Hidden Horniman Mysid

Original source

Wittmann, K. J.; Abed-Navandi, D. (2021). Four new species of Heteromysis (Crustacea: Mysida) from public aquaria in Hawaii, Florida, and Western to Central Europe. European Journal of Taxonomy. 735: 133-175. https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2021.735.1247

Contacts:

Karl Wittmann (karl.wittmann@meduniwien.ac.at), first author of the new species

Daniel Abed-Navandi (daniel.abed@haus-des-meeres.at), co-author of the new species

Jamie Craggs (jcraggs@horniman.ac.uk), aquarium curator

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1485483&pic=150585

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1485483#images

Other media:

New species of shrimp found after ‘hitchhiking’ on ocean rock to south London museum

The Cebimar Moon Jellyfish

Original source:

Lawley, J.W.; Gamero-Mora, E.; Maronna, M.M.; Chiaverano, L. M.; Stampar, S.N.; Hopcroft, R.R.; Collins, A.G.; Morandini, A.C. (2021). The importance of molecular characters when morphological variability hinders diagnosability: systematics of the moon jellyfish genus Aurelia (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa). PeerJ 9: e11954. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11954

Contact:

Jonathan Lawley (jonathan.wanderleylawley@griffithuni.edu.au), first author of the new species

Andre C. Morandini (acmorand@ib.usp.br), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1539747&pic=150587

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1539747#images

Other media:

New description increases number of known species in jellyfish genus from seven to 28

The Emperor Dumbo

Original source:

Ziegler, A., Sagorny, C. (2021). Holistic description of new deep sea megafauna (Cephalopoda: Cirrata) using a minimally invasive approach. BMC Biology 19, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-021-01000-9

Contact:

Alexander Ziegler (aziegler@evolution.uni-bonn.de), first author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1507664&pic=150589

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1507664#images

Other media:

First description of a new octopus species without using a scalpel

Seeing Inside the Newly Discovered Emperor Dumbo Octopus

New Species of Dumbo Octopus Identified Using 3-D Imaging Techniques

All hail 'Emperor Dumbo,' the newest species of deep-dwelling octopus

Scientists Just Identified a New Species of Dumbo Octopus, No Dissection Required

Marine Biologists Discover New Octopus Species in Pacific Ocean

The Yokozuna Slickhead

Original source:

Fujiwara, Y., Kawato, M., Poulsen, J.Y., Ida, H., Chikaraishi, Y., Ohkouchi, N., Oguri, K., Gotoh, S., Ozawa, G., Tanaka, S., Miya M., Sado, T., Kimoto, K., Toyofuku, T., & Tsuchida, S. (2021). Discovery of a colossal slickhead (Alepocephaliformes: Alepocephalidae): an active-swimming top predator in the deep waters of Suruga Bay, Japan. Scientific Reports. 11, 2490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80203-6

Contacts:

Yoshihiro Fujiwara (fujiwara@jamstec.go.jp), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1517698&pic=150593

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1517698#images

Other media:

'Apex predator' fish almost 5ft long found in deep sea named after sumo wrestler

Scientists stumbled onto toothy deep-sea "top predator," and named it after elite sumo wrestlers

The Quarantine Shrimp

Original source:

Park, J.-H.; De Grave, S. (2021). Two New Species and a Further Country Record of the Caridean Shrimp Genus Periclimenaeus Borradaile, 1915 from Korea (Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Zoological Studies. 60: e1. https://doi.org/10.6620/ZS.2021.60-01

Contact:

Sammy De Grave (sammy.degrave@oum.ox.ac.uk), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1480081&pic=150644

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1480081#images

The Japanese Twitter Mite

Original source:

Pfingstl, T.; Hiruta, S. F.; Nemoto, T.; Hagino, W.; Shimano, S. (2021). Ameronothrus twitter sp. nov. (Acari, Oribatida) a New Coastal Species of Oribatid Mite from Japan. Species Diversity. 26(1): 93-99. https://doi.org/10.12782/specdiv.26.93

Contact:

Tobias Pfingstl (tobias.pfingstl@uni-graz.at), first author of the new species

Images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1512258&pic=150610

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1512258#images

The Jurassic Pig-Nose Brittle Star

Original source:

O'Hara, T. D.; Thuy, B.; Hugall, A. F. (2021). Relict from the Jurassic: new family of brittle-stars from a New Caledonian seamount. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288(1953): 20210684. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0684

Contact:

Tim O’Hara (tohara@museum.vic.gov.au), first author of the new species

Ben Thuy (ben.thuy@mnhn.lu), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1515847&pic=150615

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1515847#images

Other media:

Ramari’s Beaked Whale

Original source:

Carroll, E. L.; McGowen, M. R.; McCarthy, M. L.; Marx, F. G.; Aguilar, N.; Dalebout, M. L.; Dreyer, S.; Gaggiotti, O. E.; Hansen, S. S.; Van Helden, A.; Onoufriou, A. B.; Baird, R. W.; Baker, C. S.; Berrow, S.; Cholewiak, D.; Claridge, D.; Constantine, R.; Davison, N. J.; Eira, C.; Fordyce, R. E.; Gatesy, J.; Hofmeyr, G. J. G.; Martín, V.; Mead, J. G.; Mignucci-Giannoni, A. A.; Morin, P. A.; Reyes, C.; Rogan, E.; Rosso, M.; Silva, M. A.; Springer, M. S.; Steel, D.; Olsen, M. T. (2021). Speciation in the deep: genomics and morphology reveal a new species of beaked whale Mesoplodon eueu. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288(1961). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1213

Contact:

Emma Carroll (carrollemz@gmail.com), first author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1567463&pic=150560

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1567463#images

Other media:

Video by the University of Auckland exploring the etymology of the new species

The Balloon Backpack Isopod

Original source:

Williams, J. D.; Boyko, C.B. (2021). Out on a limb: novel morphology and position on appendages of two new genera and three new species of ectoparasitic isopods (Epicaridea: Dajidae) infesting isopod and decapod hosts. Zoosystema 43(4): 79–100. https://doi.org/10.5252/zoosystema2021v43a4. http://zoosystema.com/43/4.

Contacts:

Jason Williams (Jason.D.Williams@hofstra.edu), first author of the new species

Christopher C. Boyko (cboyko@amnh.org), co-author of the new species

Image available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1484148&pic=150619

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1484148#images

Winter’s Basket Coccolithophore

Original source:

Keuter, S.; Young, J. R.; Koplovitz, G.; Zingone, A.; Frada, M. J. (2021). Novel heterococcolithophores, holococcolithophores and life cycle combinations from the families Syracosphaeraceae and Papposphaeraceae and the genus Florisphaera. Journal of Micropalaeontology 40(2): 75-99. https://doi.org/10.5194/jm-40-75-2021

Contact:

Jeremy Young (jeremy.young@ucl.ac.uk), first author of the new species

Sabine Keuter (sabine.keuter@mail.huji.ac.il), co-author of the new species

Miguel Frada (miguel.frada@mail.huji.ac.il), co-author of the new species

Images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1567453&pic=150559

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=image&tid=1567453&pic=150648

More images available at:

https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1567453#images